This May 16, 2017 photo shows the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center in Church Creek, Md. The Harriet Tubman Byway on Maryland's Eastern Shore was designed to help bring to life the famed abolitionist. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

PRESTON, Md. (AP) - Beside a quiet stream on Maryland's Eastern Shore, a 19th century brick house that once served as a way station on the Underground Railroad can bring present-day visitors to tears as they gaze at the path where escaped slaves made their way to freedom.

The Jacob and Hannah Leverton house is among 36 sites along the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway. The 125-mile route has been getting fresh attention in recent months as the nation and the world take more notice of Tubman's heritage as a hero of freedom.

Tubman, who escaped from slavery in antebellum Maryland to become a leading abolitionist, helped other slaves escape by guiding them north on the Underground Railroad and served as a Union spy during the Civil War.

"It's hard to identify with George Washington, unless you're an older white male. But when it comes to Tubman, there's so many ways that people of all backgrounds and races ... can find something that they can see in themselves that she has carried forward or she held herself," says Kate Larson, an author and historian who has written about Tubman and worked as a consultant on the byway.

___

FRESH ATTENTION

The famed Underground Railroad conductor is drawing admiration from new generations.

Plans to put her on the $20 bill have received prominent attention, stirring debate about the representation of old white historic figures on the nation's currency and the lack of women and minorities.

This year, the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution's new National Museum of American History and Culture in Washington acquired a rare photograph of Tubman in her late 40s.

In March, the $21 million Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center opened, not far from her Maryland birthplace.

___

LONG ROAD

The designated sites and nearby landscapes offer a comprehensive look into Tubman's life and journeys along the Underground Railroad, an informal network that helped escaping slaves evade capture and reach free states such as nearby Pennsylvania.

After about 18 years of planning, the first stops along the byway were designated in 2013 to coincide with the centennial of Tubman's death.

"This is just an opportunity for the world to know that Harriet has been a major part of our history in the United States of America," said Victoria Jackson-Stanley, the first black woman elected mayor of Cambridge, the county seat, not far from where Tubman was born and raised a slave. "She's a local home girl, as I like to say, but she's an icon for freedom."

___

TELEVISION REVIVAL

Tubman was featured recently in "Underground," a WGN television drama about the Underground Railroad.

Actress Aisha Hinds, who played Tubman, attributes the abolitionist's increasing prominence partly to the divided times of the present.

"I feel like, contextually, what we're living now is sort of a modern day manifestation and articulation of the times that Harriet Tubman was living and the obstacles that she transcended," Hinds said at a conference on Tubman in Cambridge, Maryland.

Meanwhile, an HBO movie with Viola Davis starring as Tubman is in the works, based on Larson's book, "Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero."

___

ACT OF DEFIANCE

The site of Tubman's first known act of defiance against slavery is one of the most popular stops on the Tubman byway.

The Bucktown Village Store has been restored at a rural crossroads believed to be where Tubman refused a slave owner's orders to help him detain another slave. When the other slave ran, the owner grabbed a 2-pound weight and threw it at him, hitting Tubman on the head and causing an injury that would trouble her for the rest of her life.

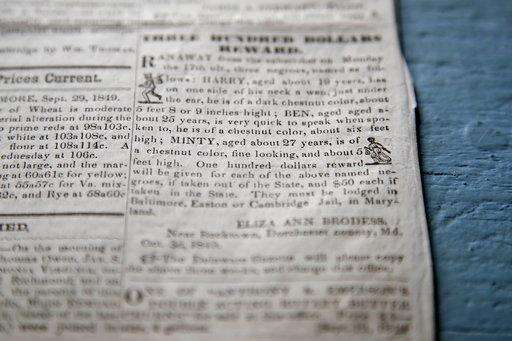

The inside still looks like a 19th century shop. The owners have some Tubman-related items, including a newspaper advertising a reward for Tubman and two of her brothers. Susan Meredith, who owns the site with her husband, says people have been stopping more frequently since the visitors' center opened nearby.

"We see people from all over the world that come to see and step in the place that she was in," Meredith says.

___

STILL DEVELOPING

Some areas with significant links to Tubman's early life are neither open to the public nor designated on the byway but could one day be purchased by the state. Some related sites have inconsistent hours, depending on when property owners are home, and are still developing under the added attention.

The Jacob and Hannah Leverton home, which is on the byway, offers mixed signals. A sign with the words "Private Drive" and "No Trespassing" stands at the foot of the drive, next to an interpretive marker that designates it as a byway stop. Still, Michael McCrea, who bought the house in the mid-1980s, is enthusiastic about the byway and accommodates visitors, even though the sign remains.

"It's fine," he says, mentioning that visitors have been undeterred by the sign to get a closer look.

McCrea has shown people around the property. Some have cried, he says, while others solemn rub the bricks of the house.

"They just can't believe that it's here," McCrea says.

In this May 25, 2017 photo, moonlight reflects off of wetlands along the Choptank River in Caroline County, Md. The Choptank and other waterways on Maryland's Eastern Shore played crucial roles in Harriet Tubman's life and the Underground Railroad, both for transportation and as conduits of information. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 12, 2017 photo, trees tower above a dirt road leading to what historians believe is the site of Harriet Tubman's birth in Dorchester County, Md. Like some other stops on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, the site itself is on private land and inaccessible to the public, and no structures tied to Tubman remain. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 25, 2017 photo, Mayor Victoria Jackson-Stanley poses for a photograph outside the Dorchester County Courthouse in Cambridge, Md., a stop on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway. "This is just an opportunity for the world to know that Harriet has been a major part of our history in the United States of America," said Jackson-Stanley, the first black woman to be elected mayor of Cambridge, not far from where Tubman was born and raised a slave and where race riots broke out 50 years ago. "She's a local home girl, as I like to say, but she's an icon for freedom and a supporter of the women's suffrage movement." (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

This May 12, 2017 photo shows a runaway slave newspaper notice for Harriet Tubman, who was called "Minty" at the time, and her two brothers at the Bucktown Village Store in Bucktown, Md. The store is a stop on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, where few physical connections to her remain. Most buildings are long gone, but the landscape looks much as it did during her time. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 25, 2017 photo, a bust of Harriet Tubman stands in the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center, a stop on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, in Church Creek, Md. As Tubmanâs role in the fight against slavery gains new appreciation in the nation and world, a historic trail in Maryland has been getting more attention. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 12, 2017 photo, Michael McCrea shows where people have come to touch his house, the former home of Jacob and Hannah Leverton, once a key stopping point for slaves seeking sanctuary on the Underground Railroad in Preston, Md. "They just can't believe that it's here," McCrea said. Today, like some other stops on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, the house is on private land. McCrea, who expresses enthusiasm for the byway, is accommodating to visitors who are undeterred by a "No Trespassing" sign at the entrance to his property. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

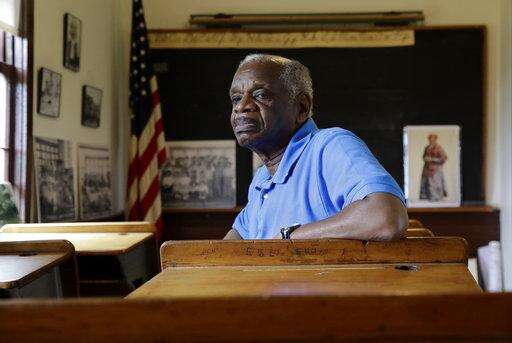

In this May 12, 2017 photo, Herschel Johnson sits inside a former one-room schoolhouse for black students known as the Stanley Institute, a stop on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, in Cambridge, Md. Johnson, who was educated in a two-room schoolhouse in a nearby community, has led efforts to restore the schoolhouse. Built in 1865 and moved to its current spot in 1867, it was run independently by the local black community and remained in use until the 1960s. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 16, 2017 photo, tourists photograph the Bucktown Village Store, a rural store building that has been restored on the spot believed to be where Harriet Tubman refused a slave owner's orders to help him detain a fellow slave, in Bucktown, Md. It was Tubman's first known act of defiance against slavery. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 16, 2017 photo, gravestones from the 1800s stand in a cemetery at Malone's Church in Madison, Md., a stop on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway. Free blacks settled around the church's land well before the Civil War, and the church itself was established by the surrounding black communities in 1864. According to oral tradition, Tubman was a member of one of these communities, living and working near the church with her free husband, John Tubman. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 12, 2017 photo, Herschel Johnson steps out of a former one-room schoolhouse for black students known as the Stanley Institute in Cambridge, Md. "We are so proud of it," Herschel said of the school that educated the local black community for nearly 100 years, and that is now a stop on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway that makes a big impression on visitors. "They are amazed that they can look back and see, especially children," Johnson said. "The questions that we get from children, for instance, we've had children ask us: 'Where is the gym? Where do you eat lunch?" (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this May 12, 2017 photo, Michael McCrea stands under a canopy of trees on his property in Preston, Md. From the tree line, runaway slaves made a short walk across an open cornfield to a 19th-century brick house that was a key stopping point for the Underground Railroad on Maryland's Eastern Shore. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press