In this March 29, 2017 photo, a forged painting purported to be the work of artist Mark Rothko is displayed during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The new exhibition offers would-be sleuths a firsthand look at how experts detect high-priced fakes and forgeries, which can rock the rarified world of fine arts. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

GREENVILLE, Del. (AP) - A painting with problematic pigment. A Chanel suit dressed up with acetate trim instead of silk. A Stradivarius violin that, well, just doesn't sound right.

They're all part of a new exhibit at Delaware's Winterthur Museum that offers would-be sleuths a firsthand look at how experts detect the high-priced fakes and forgeries that rock the rarified world of fine arts.

"Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes," illustrates the ongoing battle that pits clever forgers and con men against equally determined art conservationists and historians.

The exhibition, which includes documentary film and a lecture series, opens Saturday and runs through Jan. 7.

The weapons used by art gallery gumshoes who dedicate themselves to uncovering fraud include historical documentation of ownership, or provenance; scientific analysis; and "connoisseurship," a systematic but nonetheless subjective examination of an object for perceived consistencies or inconsistencies with one known to be genuine.

In a small gallery at Winterthur, best known for its collection of American decorative arts, the abstract expressionist painting by Mark Rothko that greets visitors might seem out of place.

Until you discover it's a forgery that was part of the largest art fraud in American history, in which New York art dealer Glafira Rosales admitted participating in a 15-year scam that fooled art collectors into buying more than $60 million of counterfeit paintings attributed to the likes of Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

"They had a mysterious provenance ... they came out of nowhere," said art sleuth and exhibit co-curator Colette Loll, founder and director of Art Fraud Insights, a Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm.

The scandal, which resulted in the closing of New York's Knoedler & Co. art gallery, should serve as a cautionary tale, Loll suggested.

Rosales was sentenced earlier this year to nine months of house arrest and three years' probation, but Loll noted that no one was ever prosecuted for actually creating the forgeries.

"In the U.S., we don't have anti-forgery laws, unlike many other European countries," Loll said, explaining that the crime is in representing a forgery or fake as the genuine item.

"It's the intent to deceive," she said.

While intent is a key element, the motivations behind art fraud can vary, including financial gain, an artist's frustration about not being appreciated, a desire for attention, or simply the challenge of trying to fool the experts.

The exhibit, in which fakes and forgeries can be seen alongside authentic objects, offers a rare look into the tools and techniques used by Winterthur's Scientific Research and Analysis Lab. They include a variety of spectrometers that use infrared light, ultraviolet light and x-rays to analyze the chemical composition of materials and help determine, for example, that the solder used in a lampshade long thought to be a genuine Tiffany creation contained zinc instead of lead, confirming that it was a fake.

"A very, very good fake," acknowledged exhibit co-curator Linda Eaton, director of collections and senior curator of textiles at Winterthur.

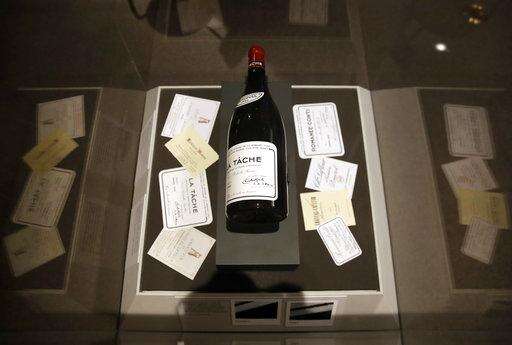

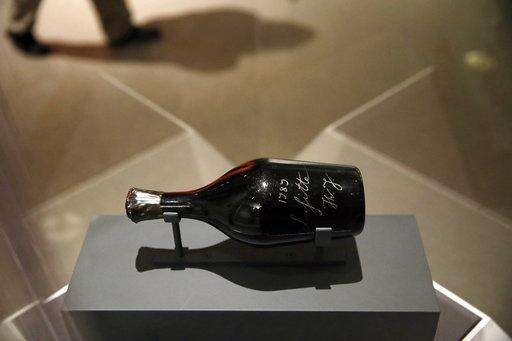

Not surprisingly, even experienced collectors can be fooled by fakes, including furniture purchased by Winterthur founder Henry Francis du Pont, and millions of dollars of counterfeit fine wine, including bottles that purportedly belonged to Thomas Jefferson, bought by billionaire Bill Koch.

"I think one of the takeaways that we want to make sure people have is how all of us need to be humbled and need to keep an open mind," Eaton said.

In other words, we may never know whether vampires are real, but a little sleuthing might help determine the authenticity of a 19th-century "vampire killing kit."

This March 29, 2017 photo shows a counterfeit Hermes Berkin luxury handbag during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The exhibition's items on display, both genuine and fake, extend well beyond paintings and fine art, to include high fashion, furniture, sports memorabilia, even postage stamps and weather vanes. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this March 29, 2017 photo, a forged painting purported to be the work of artist Mark Rothko is seen past exhibit co-curator Colette Loll during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The painting was part of an art dealer's 15-year scam that fooled art collectors into buying more than $60 million of counterfeit paintings attributed to Rothko and others. The painting, created by a man in Queens, will offer visitors a firsthand look at how experts detect high-priced fakes and forgeries. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

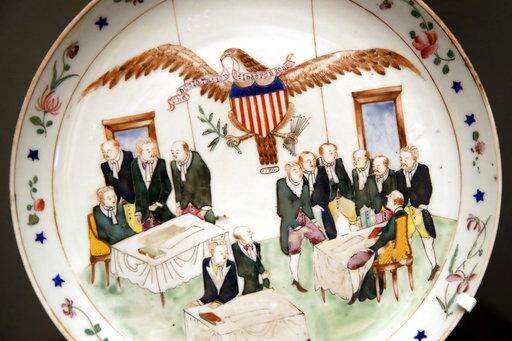

In this March 29, 2017 photo, artwork on a porcelain plate depicts a scene from early American history during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The plate was part of a collection purchased by the museum's founder, Henry Francis du Pont, from a missionary returning from China in 1948. Their age and origin remained obscure until scientific analysis performed in 2004 suggested that the collection was created in the early 20th century. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this March 29, 2017 photo, a violin purported to be a highly sought-after Stradivarius is seen on display during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. While experts determined that the violin was likely made in the 19th century, its Stradivarius label turned out to be fake. The exhibition includes a broad range of objects that illustrate the ongoing battle pitting clever forgers and con men against equally determined art conservationists and historians. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

This March 29, 2017 photo shows a forged 1990 bottle of DRC La Tache wine that was sold to billionaire Bill Koch alongside assorted forged wine labels during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. Under high magnification, experts determined that the label on the bottle was photocopied. The exhibition includes a broad range of objects that illustrate the ongoing battle pitting clever forgers and con men against equally determined art conservationists and historians. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this March 29, 2017 photo, a genuine lampshade created by Tiffany Studios in the early 1900s, left, stands alongside a forgery created in the second half of the 20th century during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The exhibition illustrates the ongoing battle that pits clever forgers and con men against equally determined art conservationists and historians. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

This March 29, 2017 photo shows a detail of a painting purported to be the work of artist Jackson Pollock is seen during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. A New York painter admitted in 2014 to fabricating the historical documentation of ownership, or provenance, of the painting, but not to forging the work itself. The motivations behind art fraud can vary, including financial gain, an artist's frustration about not being appreciated, a desire for attention, or simply the challenge of trying to fool the experts. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this March 29, 2017 photo, a bottle of wine purported to have belonged to Thomas Jefferson is seen on display during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. Deemed a fake, the owner claimed that the bottle was found behind the brick wall of a house in Paris, where Jefferson lived between 1784 and 1798. But Jefferson never lived in the neighborhood where the bottle was purported to have been found. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press

In this March 29, 2017 photo, a counterfeit Chanel houndstooth suit, right, is displayed alongside a suit from Chanel's spring/summer 1971 collection during a press preview of "Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes" at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The items on display at the exhibition, both genuine and fake, extend well beyond paintings and fine art, to include high fashion, furniture, sports memorabilia, even postage stamps and weather vanes. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

The Associated Press