A customer walks into the Frosty Freeze restaurant in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Everyone in town comes to this diner for nostalgia and homestyle cooking and, recently, news reporters come from all over the world to puzzle over politics. Because Elliott County, a blue-collar union stronghold, voted for the Democrats in each and every presidential election for its 147-year existence. Until Donald Trump came along and promised to wind back the clock. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

SANDY HOOK, Ky. (AP) - The regulars amble in before dawn and claim their usual table, the one next to an old box television playing the news on mute.

Steven Whitt fires up the coffee pot and flips on the fluorescent sign in the window of the Frosty Freeze, his diner that looks about the same as it did when it opened a half-century ago.

People like it that way, he thinks. It reminds them of a time before the world seemed to stray, when coal was king and the values of the nation seemed the same as the values here, in God's Country, in this small county isolated in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

Elliott County, a blue-collar union stronghold, voted for the Democrat in each and every presidential election for its 147-year existence - until Donald Trump promised to wind back the clock.

"He was the hope we were all waiting on, the guy riding up on the white horse. There was a new energy about everybody here," says Whitt.

"I still see it."

Despite the president's dismal approval ratings and lethargic legislative achievements, he remains popular here, a region so battered by the collapse of coal it became the symbolic heart of Trump's white working-class base.

The frenetic churn of the national news scrolls soundlessly across the bottom of the diner's television screen, rarely registering. When it does, Trump doesn't shoulder the blame - because the allegiance to him among supporters here is as emotional as it is economic. It means God, guns, patriotism. It means tearing down the political system that neglected them in favor of cities that feel a world away. On those counts, they believe Trump has delivered; he's punching at all the people who let them down.

"One thing I hear in here a lot is that nobody's gonna push him into a corner," says Whitt, 35. "He's a fighter. I think they like the bluntness of it."

He plops down at an empty table, drops a stack of mail onto his lap and begins flipping through the envelopes.

Whitt and his wife, like many people here, cobble together a living with a couple jobs each because there aren't many options better than minimum wage. Outside of town, roads wind past rolling farms that used to grow tobacco before that industry crumbled too, then up into the hills of Appalachia, with its spectacular natural beauty and grinding poverty that has come to define this region in the American imagination.

Whitt supported Trump because of his stand on social issues like guns and religion, and also his promise to revive the working-class economy. A third of people in Elliott County live in poverty. Just 9 percent of adults have a college degree. Once, they made up for that with backbreaking labor that workers traveled dozens of miles to neighboring counties or states to do, but those jobs are harder to find. So many rely on government assistance, and Whitt's grown frustrated that he and his wife foot the bill and can't get ahead, despite working 12 hours a day.

Whitt doesn't blame Trump for failures like Republicans' inability to repeal the Affordable Care Act. He blames the "brick wall" in Washington, all the politicians who have left places like this behind. And he and his neighbors cheer Trump for moves like scrapping regulations designed to curb carbon emissions, which they condemn for leading to mining's decline.

Coal jobs have ticked up slightly since Trump took office, but industry analysts dismiss Trump's pledges to resuscitate the industry as pie in the sky. Coal has been on the decline for decades for reasons outside of regulation: far cheaper natural gas, mechanization, thinning Appalachian seams. The region has relied on programs like the Appalachian Regional Commission and Economic Development Administration that provide money for job-training, anti-poverty efforts and beautification initiatives aimed at transitioning to a tourism economy. Trump proposed a budget that wipes out those programs.

Still, retired pipefitter Wes Lewis says he's seeing signs that the region is coming back to life. A few months ago, he saw four brand-new coal rigs going through town. He's noticed new trucks in driveways, which he takes as evidence that his neighbors are feeling confident.

He thinks the mines will soon roar back to life, and if they don't, he believes they would have if Democrats and Republicans and the media - all "crooked as a barrel of fishhooks" - had gotten out of the way. Likewise, if there isn't a wall built on the Mexico border, it won't be because Trump didn't try, he says.

"He's already done enough to get my vote again, without a doubt," he says.

Others find Trump's promises dangerous.

Gwenda Johnson, retired after nearly 40 years in community development, says it's time to acknowledge the painful fact that coal will never be what it was, no matter what Trump pledges.

"I fear that when they finally realize that Donald Trump is not the savior they thought he was - if they ever come to that realization - the morale in these rural areas will be so low that they will not ever put faith in anyone again," she says.

But Lewis is sticking by him, because he feels like he has no other choice.

"Here's the big thing," he says, "if Trump lies to us, it won't be anything different than what the rest of them always did."

___

AP data journalist Angeliki Kastanis contributed to this report. Follow Claire Galofaro on Twitter at https://twitter.com/clairegalofaro

Steven Whitt, left, opens the Frosty Freeze restaurant he runs with his wife as regular customers wait outside in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. The regulars amble in before dawn and claim their usual table, the one next to an old television set playing the news on mute. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Steven Whitt opens the Frosty Freeze restaurant that he runs with his wife in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. Whitt fires up the coffee pot and flips on the fluorescent sign in the window, his diner that looks and sounds and smells about the same as it did when it opened a half-century ago. Coffee is 50 cents a cup, refills 25 cents. The pot sits on the counter, and payment is based on the honor system. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

A newscast showing President Donald Trump plays on an old television set as customers play cards in the Frosty Freeze restaurant in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Many families here can trace their ancestry back generations on the same land. Almost everyone is white, and almost everyone is Christian. At the Frosty Freeze, a plaque with a Bible verse hangs under the television, from the book of Romans: "Owe no man nothing but to love one another." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Old photos curled at the edges decorate a pin up board in the Frosty Freeze restaurant in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. The restaurant reminds the locals of a time before the world seemed to stray away from them, when coal was king and the values of the nation seemed the same as the values here, in God's Country, in this small county isolated in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla Whitt, right, takes off a helmet her nine-month old son, Tommy Joe, must wear after being born with a rare condition where his skull bones didn't fuse together properly, at their home in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. The helmets cost around $4,000. They add it to a growing pile of bills that's already surpassed $40,000 since Tommy Joe was born. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla Whitt works in the Frosty Freeze restaurant she runs with her husband next to a picture of their nine-month old son, Tommy Joe, in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. The Whitts pay almost $800 a month for insurance. But when they took Tommy Joe to a surgeon in Cincinnati, they learned it was out of network and they'd have to pay out of pocket. At the hospital they were told that if they'd been on an insurance program for the poor, it would have all been free. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Main Street, center, cuts through Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Despite the president's plummeting approval ratings, he remains profoundly popular in these mountains, a region so badly battered by the collapse of the coal industry it became the symbolic heart of Trump's white working-class base. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Dale Ferguson stands in his hunting cabin decorated with deer he's killed, mounted on the wall, as he prepares to go out on a hunt in Isonville, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. Ferguson has three priorities in life and in politics, in this order: God, guns, family. Like it used to be, he says. And now he sees himself reflected in America's president. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Dale Ferguson heads out into the woods to hunt for deer with a bow and arrow in Isonville, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. So far he gives President Trump two thumbs-up, mostly for fighting the culture wars. He dismisses everybody up in arms over Trump not being "presidential." That's what he liked about him in the first place. "It wouldn't bother me a bit if a guy ran that was dressed like me, and I look like a heathen," he says, gesturing to his camo pants tucked into his boots. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Dale Ferguson sits in a tree while hunting for deer with a bow and arrow in Isonville, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. Ferguson has three priorities in life and in politics, in this order: God, guns, family. Like it used to be, he says. And now he sees himself reflected in America's president. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Reggie Dickerson looks out over his backyard at his home in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. "I want him to come here. Donald Trump owes it to Elliott County," he says. "I would love for him to come here, see the people, what's been taken from them, and help restore it." His community suffered a one-two punch, he says. It lost the tobacco industry, and then coal. Families were left dependent on welfare. And now they're depending on Trump to revive the coal business _ and manufacturing across the country _ and put people back to work. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Reggie Dickerson sits near a portrait of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, next to a photo of his son, and a Christmas tree at his home in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. To Dickerson, President Barack Obama has come to represent all the things he believes have gone awry. There are the environmental regulations to try to curb carbon emissions that many blame for the decimation of the coal business. But Obama has also become a symbol to him of a changing nation: gay marriage, immigrants, lost blue collar jobs that left families on welfare, a widely-held fear that the government would take their guns if it had its way. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Dwight Whitley plays guitar with friends during one of their weekly country and bluegrass jam sessions in Isonville, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. Dwight was, like most people here, a registered Democrat for 48 years, until President Barack Obama was elected and he got fed up with the party, which he says is for "abortionists and gun grabbers for gay rights." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Dwight Whitley, center, plays the banjo with Jackie Lewis, left, on the guitar and Lewis' brother, Wendell, on the bass during one of their regular country and bluegrass jam sessions in Isonville, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. He plays every week with lifelong friends, some who aren't Trump supporters. "Trump is working hard and doing some really good things," he says. He likes his tough talk, his stance on guns and immigration and religion. He says he's seen coal trucks on the roads, and that gives him hope that the blue-collar economy is improving like Trump promised it would. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Dwight Whitley walks on stairs near a portrait of his late brother, county and bluegrass musician Keith Whitley, in his home in Isonville, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Dwight is something of a local celebrity. He's a banjo player and the brother of bluegrass legend Keith Whitley so beloved here that the date he died can be rattled off by many from memory _ it is, for them, like the day Elvis died in the rest of the world. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Terry Stinson, left, talks with Deborah Harmon at the Frosty Freeze restaurant in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Stinson, a retired construction worker, comes to the Frosty Freeze almost every evening for dinner since his wife died. "I damn sure didn't vote for Trump. I'd rather walk through hell wearing gasoline britches," he barks. The country has been sold trickle-down economics before, he says, "And it's never trickled down to Sandy Hook. Why would it this time?" (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

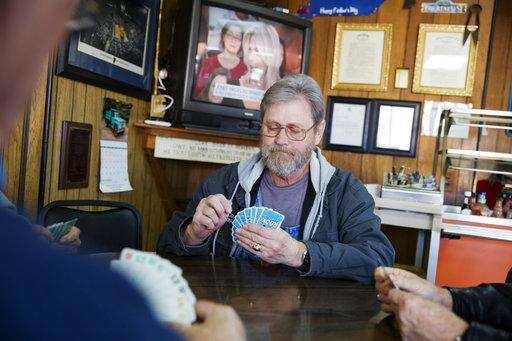

Wes Lewis plays cards with fellow regulars at the Frosty Freeze restaurant in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. "He's already done enough to get my vote again," Lewis says. He thinks the mines and the factories will soon roar back to life, and if they don't, he believes they would have if Democrats and Republicans and the media _ all "crooked as a barrel of fishhooks" _ had gotten out of the way. What Lewis has now that he didn't have before Trump is a belief that his president is pulling for people like him. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla Whitt, right, talks with employee Angela Whitley in the Frosty Freeze restaurant Whitt runs with her husband in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. Whitt isn't quite sure how much faith to put in Trump to improve things in her own life. She liked him on "The Apprentice." She liked that he was funny and knew how to make money, and so she thinks everyone ought to calm down and give him a chance. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Steven Whitt checks the date on a tombstone he needs for a document as part of his funeral home business in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. In addition to running a restaurant, also owns a local funeral home, and he's the county coroner - elected as a Democrat. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Steven Whitt dusts off his guitar in preparation to perform a song during a funeral service at the funeral home he runs in Sandy Hook, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Whitt, a lifelong Democrat, went from supporting President Barack Obama to buying a "Make America Great Again" cap that he still keeps on top of the hutch. Many of their welfare-dependent neighbors, he believes, stay trapped in a cycle of handouts and poverty while hardworking people like him and his wife pay their own way and can't get ahead. "Where's the fairness in that?" he asks. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla Whitt, right, carries her nine-month old son, Tommy Joe, while taking him to a doctor's appointment with her husband, Steven Whitt, left, in Morehead, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. They pay almost $800 a month for insurance. But when they took their baby to a surgeon in Cincinnati, they learned it was out of network and they'd have to pay out of pocket. At the hospital they were told that if they'd been on an insurance program for the poor, it would have all been free. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla Whitt, left, holds her nine-month old son, Tommy Joe, as during a checkup with Dr. Brandy Fouch in Morehead, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. Tommy Joe was born with a rare condition where his skull bones didn't fuse together properly. He's had to wear helmets that cost about $4,000 each so his bones grow back together. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla and Steven Whitt shop for holiday cookies with their nine-month old son, Tommy Joe, in Morehead, Ky., Thursday, Dec. 14, 2017. The Whitts, like many people here, cobble together a living with a couple jobs each _ sometimes working 12 or 15 hours a day _ because there aren't many options better than minimum wage. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press

Chesla Whitt kisses her nine-month old son, Tommy Joe, as she puts him to bed for the night at their home in Sandy Hook, Ky., Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2017. Tommy Joe was born with a rare condition where his skull bones didn't fuse together properly. He's had to wear helmets that cost about $4,000 each so his bones grow back together. They add it to a growing pile of bills that's already surpassed $40,000 since he was born. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The Associated Press