Jonelson Princeton, 7, who survived cholera as a newborn, peers out from inside his home which was once used as an office, on a former UN base where he lives with his parents and grandmother in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

MEILLE, Haiti (AP) - Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed nearly 10,000 people, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease.

It was one of the world's worst outbreaks of the preventable disease in recent history, sickening more than 850,000 people in a country of 11 million that had not reported a cholera outbreak for more than a century. The last confirmed case in Haiti was reported in January 2019, but the epidemic's aftermath is still felt across much of the country, most acutely in places like Meille, where Haitians remain exposed to unsanitary conditions and are often unable to make up for the loss of income after the main breadwinners of their family died.

'œWe're not getting support from anyone,'ť said Lizette Paul, a 48-year-old mother of four children whose brother died in 2012 from the disease. They had to borrow hundreds of dollars from a neighbor with interest to bury him, and since then, Paul has resorted to washing clothes for people in the same river that became contaminated, charging $12 a month, not enough to care for her loved ones. Her brother had earned more by providing informal public transportation aboard a colorful bus known as a tap-tap.

'œHe was the backbone of the family,'ť Paul said.

Cholera was introduced to Haiti's largest river in October 2010 by sewage from a nearby base of U.N. peacekeepers from Nepal. Six years later, the U.N. acknowledged it played a role in the epidemic and had not done enough to help fight cholera in Haiti, but the organization has not specifically said it introduced the disease.

The disease spread quickly in a country that just nine months before the epidemic began had been devastated by the January 2010 earthquake. Cases spiked given that more than a third of the population lacks basic drinking water services and two-thirds have limited or no sanitation services, according to the Pan American Health Organization.

In a letter sent to senior staff when he left the U.N. in December, former U.N. Assistant Secretary-General Andrew Gilmour called it an 'œavoidable tragedy'ť that 'œmay rank as the single greatest example of hypocrisy in our 75-year history.'ť

During a speech earlier this month at Harvard University, Gilmour talked publicly about the situation for the first time, noting that many felt the U.N. could have accepted moral responsibility much earlier and shown greater compassion.

'œThe low-water mark has been the U.N.'s continued legal response to Haiti,'ť he said.

One of the biggest concerns a decade after the epidemic began is the ongoing lack of funds to help those affected.

A group of U.N. rights experts sent a letter to Secretary-General António Guterres earlier this year, saying that roughly 5% of the $400 million pledged in 2016 had been raised. They also noted that a U.N. plan to provide direct assistance to victims and families was 'œquietly repackaged'ť as support to affected communities without consulting the victims or taking their specific needs into consideration.

The Office of the Special Envoy for Haiti countered in a response sent to The Associated Press that the international community has spent more than $705 million to fight cholera, including more than $80 million mobilized by U.N. agencies since 2016. It said the money has funded water and sanitation infrastructure and led to the creation of epidemiological and surveillance systems, adding that the U.N. is one of the largest funders of Haiti's national water and sanitation agency.

However, the office noted the U.N. has been able to target around 25 of more than 130 communities most directly affected by cholera because of a lack of funds. In a recent letter to leaders around the world, the secretary-general asked for more contributions for cholera victims.

'œDespite the gains made to stop transmission, much more work remains to be done to support them, as well as the hardest hit communities,'ť the U.N. said in a statement Wednesday.

On Sunday, more than 200 people filled a church in Mirebalais to decry the situation, honor those who died from cholera and celebrate those who survived, including 48-year-old Fritznel Prenus. The moto-taxi driver said he didn't think he would recover from a disease that is easily treatable but can kill someone within hours if unattended.

'œA lot of people around me didn't survive,'ť he recalled of the scene at the hospital in Mirebalais where he was treated. 'œThis sickness, this is something I don't wish upon anyone.'ť

After the church service ended, dozens of those attending made the two-hour trek under a harsh sun to Meille and the nearby, now abandoned U.N. base to demand compensation. Among them was 72-year-old Simon Louis, who also survived cholera and is a member of a local group pursuing reparations.

'œI don't want justice just for me,'ť he said. 'œI would like to have justice for the ones who passed away. For the people who left loved ones who are suffering.'ť

Haiti will be declared cholera-free by the World Health Organization only after reaching three consecutive years with no new cases, but some wonder whether the milestone will be reached.

Dozens of people in Meille still walk every day to the river that once carried cholera with a toothbrush in hand or an empty jug to fill up with water they will drink.

'œI don't have a choice,'ť said 15-year-old Vanessa Jean-Baptiste. 'œThis is the only water that's not far from here.'ť

___

Lederer reported from New York.

Geraldine Pierre 14, front, eats as she takes a break from washing clothes with her family in the Meille River near a former UN base in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Cholera survivors carry the Creole message: "10 years, victims of cholera are tired" as they march to the former UN base in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Cholera survivors attend Mass at a Catholic church to commemorate 10 years since the cholera outbreak in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Eight-year-old Naffetalie Paul holds up an ID and photo of her late father Fritznel Paul, who died of cholera at age 39 when she was a newborn, as she stands in the doorway of her aunt's home where her father supported his two sisters and their six children in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Cholera survivors walk along the Meille River to the former UN base where they will leave flowers as they commemorate 10 years since the cholera outbreak in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

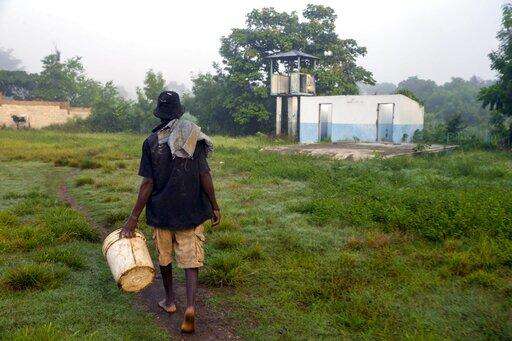

Lukcner Josapha, 43, walks through the former UN base to the Meille River to collect rocks he'll use to build his home outside the base in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Naffetalie Paul, 8, is helped by her Aunt Lizette Paul from the doorway where her cousin Lovenyda Paul sits near her great-grandmother Dieumene Bastien, who lost her son Fritznel Paul, Naffetalie's father, to cholera 13 years ago in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Jonelson Princeton, 7, left, who survived cholera as a newborn, stands near his sister Ritchina Princeton, center, and other siblings where they live with their parents and grandmother in what was once an office on the former U.N. base in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Malaika Pierre, 5, waits for her mother to wash clothes in the Meille River, in front of the former UN base in Mirebalais, Haiti, Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press

Malaika Pierre, 5, walks between her mother Rose Andre Leon, left, and cousin Geraldine Pierre on the former UN base as they make their way to the Meille River to wash clothes in Mirebalais, Haiti, at sunrise Monday, Oct. 19, 2020. Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept through Haiti and killed thousands, families of victims still struggle financially and await compensation from the United Nations as many continue to drink from and bathe in a river that became ground zero for the waterborne disease. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

The Associated Press