Doug Biggers, whose son, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, pauses in his home office next to a framed photo of his son wearing his favorite jersey, in La Quinta, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. For months, Doug sat silently. He pretended when he could that it wasn't real. He nailed two coat hooks to the wall in his home office and hung Landon's jackets there, as though his son had just stopped by. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

LA QUINTA, Calif. (AP) - There is nothing left to do, no more frantic phone calls to make, no begging or fighting that can fix this because the worst thing that could happen already has, so Doug Biggers settles into his recliner and braces for his daughter's voice to echo through his head.

"Keep going, Daddy," she's saying.

It's been months since they knelt over his 20-year-old son on the bedroom floor. But in these quiet moments, those words haunt him.

"Don't give up," Brittaney had said as he thrust down on his son's chest - his skin already blue, his hands already clenched. The 911 operator counted out compressions, so he'd pushed and pushed, trying not to cry or be sick, trying not to imagine his son as a little boy, before his addiction turned their lives into a series of crises like this one: sheer terror and futile thrashing to save him.

The paramedics arrived and shook their heads. Brittaney glanced at the clock on the stove to record the moment hope was lost: 11:43 a.m. on Nov. 21, 2017.

Landon Biggers became one of 70,237 Americans dead from overdose that year, most of them killed by opioids. As the crisis barrels into its third decade, opioids alone have claimed more than 400,000 lives. Each left behind a family like this one.

In an instant, the yearslong cycle of treatment centers and jail cells, late-night phone calls, holes punched in walls, emptied 401(k)s - it was all over. And a father, mother and sister were left to torment over what they should have done differently or better or sooner.

There are hundreds of thousands of families like them, and dozens more made each day, as the country continues struggling to contain the worst drug crisis in its history. They suffer in solitude, balancing sorrow with relief, shame with perseverance, resentment with forgiveness.

"I couldn't save him," Doug cries now, four words he's repeated again and again.

His wife, Mollie, is on the couch, watching a video of her son shouting at her just to hear his voice again. Brittaney, 28, flops down next to her, having just worked up the will to get out of bed, a hopeful step because some days she can't.

Brittaney used to worry that her father would die from the stress of Landon's addiction. Now she worries he will die from grief. For months after Landon died, Doug sat mostly silently, staring at the box of his son's ashes they store on a shelf above the television, so he'd be here with them.

"I'm scared to lose you," Brittaney would tell him.

"I'm not going anywhere, sweetie," he'd say.

The family had thought for years that they must be the only ones living this nightmare. Mollie dreaded her own house. She'd turn the corner into their subdivision and her throat would be on fire. She swallowed antacid tablets by the handful. So much had happened that anything seemed possible.

There were arrests, car accidents and armed drug dealers that broke into the house. Landon had punched and fought when he was desperate for drugs, so they installed locks on their bedroom doors. He stole from them, so they bought a safe. They tried psychiatrists, medications. Their mission to save him had been so all-consuming, they realized only after it ended that they were just one part of a disaster unfolding all around them.

Brittaney stormed into the house one recent morning. She'd just learned that another friend had overdosed and died, and now she has to count on her fingers how many people she's lost. Her brother, seven friends.

Doug imagines those parents staying up all night, like he did, desperately trying to manage a system that seemed incomprehensibly broken.

"Any other health crisis that had this many people dying from it, this entire country would be up in arms," he says. "But so many people still view addiction as a moral issue: You're not strong, or you don't have self-control."

"Or you have bad parents," his wife moans.

Now he reads everything he can find about the epidemic, and his shame is morphing into anger. He can't watch the news, because it reminds him that the world is marching on in the face of calamity. The vastness of it overwhelms him, but it also provides cold comfort: They aren't alone, not even close.

Doug had a dream one night that jolted him out of bed. They were all at the beach. Landon was sitting on the ground, facing the water. He kept calling Landon's name, but he wouldn't turn around. He never saw his face.

Was he forgetting his own son?

He realized when he awoke that his great fear is that Landon is nowhere, just gone, doomed by his addiction to leave no legacy.

"I can't keep doing nothing," Doug thought, and he climbed out of bed that morning and started searching the internet. He called Denise Cullen, who runs an organization called GRASP, for parents of the dead from addiction. He said he needed to do something so that his son's life might not be meaningless.

This deep into the opioid crisis, Cullen gets dozens of these calls each week, as grieving parents start looking for a new purpose now that their old one - saving their child - has failed.

Cullen told Doug he'd have to wait; her organization doesn't let parents begin support groups for at least a year after losing a child. Her own son died 10 years ago, and for that first year after she sat alone in the dark, just staring. It's usually not until the second year that parents realize how bad the grief can get, she says.

As this past Nov. 21 approached, they dreaded going from the first after to the second. They struggled over what to call it. "Anniversary" seems celebratory.

They considered going out of town but chose instead to pretend it was just another day.

Brittaney went to work, and Mollie kept herself busy trying to calculate where her son's name would fall in a chronological list of the 70,237 dead in 2017: Some 62,400 died before him and some 7,600 after. She thought if she could turn it into a math problem, maybe it might make some sense, but it didn't.

Doug carted the box of Landon's ashes around with him. He sat it on his desk as he worked in his home office and put it in the passenger seat as he tooled around town running errands.

"I hung out with Landon today," he told his family, before he put the box back on its shelf, in the living room, close by.

___

Click here for more on Cullen's group, GRASP, and here for additional resources on addiction and recovery.

___

AP National Writer Claire Galofaro has reported for years on the opioid crisis across America. Follow her on Twitter at @clairegalofaro or reach her at cgalofaro@ap.org

Mollie Biggers, center, looks at her husband, Doug, as he heads to his home office to take a business call in La Quinta, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. The Biggers went broke sending their son, Landon, to every type of treatment they could find, including one that promised to teach responsibility through raising a puppy; he named his Angel because he said she'd saved him. But now there isn't much left to do but stare at the box of his ashes on a shelf above the television, hidden behind a smiling photo of the family they always wanted but never really were. The 20-year-old died of opioid overdose in 2017. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

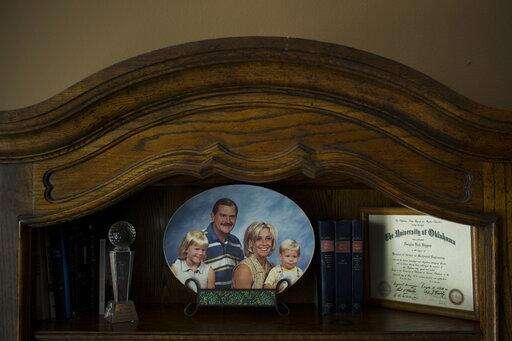

Landon Biggers sits on his motherâs lap in an old family photo in his fatherâs home office in La Quinta, Calif., on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. When he was little, he liked to dress up in costumes and decorate the house for holidays. They thought heâd grow up to be a set designer for the movies. He died in 2017 of a heroin overdose at the age of 20. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

A to-do list written on a piece of paper by Landon Biggers is lit by the sunlight at his parents' home in La Quinta, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. The 20-year-old, who died of opioid overdose in 2017, became one of 70,200 Americans dead from overdose that year, plus the 64,000 the year before. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Doug Biggers, whose 20-year-old son, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, pauses in a room where Landon died in La Quinta, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. For years Doug lived in shame, keeping Landon's addiction secret. He wasn't ashamed of his son but rather himself. Co-workers would talk about their children, going to college, getting married. Then they'd ask about his. "How do you explain he's living in his car in a Walmart parking lot and trapped in a cycle of drug use and despair?" he asks. "How broken was this family that this could happen?" (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Brittaney Biggers, whose 20-year-old brother, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, smells a football jersey her brother used to wear in La Quinta, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. âIt still smells like him,â she says. She had moved in with her parents to save money for her own apartment and planned to stay a couple months. Then her brother died, and she picked up a second job at a bar so she could work six days a week and be so tired on the seventh she wouldn't have to face it. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Doug Biggers, whose 20-year-old son, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, looks at an unopened package containing the ashes of his son in La Quinta, Calif., on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. They considered sprinkling them in the ocean, but then heâd be gone forever. Instead they moved the box to the living room, so heâd be with them, and hid it behind a picture, so they could pretend sometimes that he wasnât. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Brittaney Biggers, right, whose 20-year-old brother, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, is embraced by Abigail Collins, center, and Dana Dukovan outside a bar in La Quinta, Calif., on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. "My house makes me sick," Brittaney says. âItâs so quiet here now, I can physically feel his absence. Itâs like silence that slaps you in the face.â She had moved in with her parents to save money for her own apartment and planned to stay a couple months. Then her brother died, and she picked up a second job at a bar so she could work six days a week and be so tired on the seventh she wouldn't have to face it. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

A bird flies in the distance behind Mollie Biggers as she waits in a restaurant to meet the girlfriend of her deceased son, Landon, and their 2-year-old daughter in Huntington Beach, Calif., on Wednesday, Aug. 15, 2018. Mollie and her husband try to see Aubrey as often as they can because she helps them feel connected to their lost son. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

The late afternoon sunlight shines through the window of the room in La Quinta, Calif., Monday, Aug. 13, 2018, where 20-year-old Landon Biggers died of an opioid overdose in 2017. He became one of 70,200 Americans killed by an overdose that year, plus the 64,000 the year before. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Landon Biggers' longtime girlfriend, Megan Dealbert, reads a bedtime story to their daughter, Aubrey, in La Quinta, Calif., on Friday, Aug. 31, 2018, in the same room where Landon died from an opioid overdose. Dealbert, now a single mother, is raising their baby daughter alone. Her half-sister also died of an overdose a year before Landon. Her father, Daniel, buried her in the cemetery plot that had been meant for him. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Doug Biggers and wife, Mollie, whose 20-year-old son, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, quietly pass time in the living room of their home in La Quinta, Calif., on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. They joined the growing sorority of families left to torment over what they should have done, or shouldnât have done, or done differently, or better, or sooner. There are hundreds of thousands of families like them, and dozens more made each day, as the country continues struggling to contain the worst drug crisis in its history. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Doug Biggers, whose 20-year-old son, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, breaks down while talking about his son in La Quinta, Calif., on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. For years Doug lived in shame, keeping Landon's addiction secret. He wasn't ashamed of his son but rather himself. Co-workers would talk about their children, going to college, getting married. Then they'd ask about his. "How do you explain he's living in his car in a Walmart parking lot and trapped in a cycle of drug use and despair?" he asks. "How broken was this family that this could happen?" (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Doug Biggers, whose 20-year-old son, Landon, died of opioid overdose in 2017, holds the backyard door open for Landon's 2-year-old daughter, Aubrey, Friday, Aug. 31, 2018, in La Quinta, Calif. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press

Mollie Biggers holds the hand of her deceased son's 2-year-old daughter, Aubrey, while spending time together at Huntington Beach, Calif., on Wednesday, Aug. 15, 2018. Once her son started taking drugs as a teenager, the crises came so fast. He was in rehab by the time he was 15. He took anything he could find: Xanax, pain pills, medications Mollie was prescribed as she battled cancer. The 20-year-old died of opioid overdose in 2017. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The Associated Press