In this April 1942 photo made available by the Library of Congress, children at the Weill public school in San Francisco recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. (Dorothea Lange/U.S. War Relocation Authority via AP)

The Associated Press

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) - Satsuki Ina was born behind barbed wire in a prison camp during World War II, the daughter of U.S. citizens forced from their home without due process and locked up for years following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to desolate camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. Thousands were elderly, disabled, children or infants too young to know the meaning of treason. Two-thirds were citizens.

And now, as survivors commemorate the 75th anniversary of the executive order that authorized their incarceration, they're also speaking out to make sure that what happened to them doesn't happen to Muslims, Latinos or other groups.

They're alarmed by recent executive orders from President Donald Trump that limit travel and single out immigrants.

In January, Trump banned travelers from seven majority Muslim nations from entering the U.S., saying he wanted to thwart potential attackers from slipping into the country. A federal court halted the ban. Trump said at a news conference Thursday that he would issue a replacement order next week.

"We know what it sounds like. We know what the mood of the country can be. We know a president who is going to see people in a way that could victimize us," said Ina, a 72-year-old psychotherapist who lives in Oakland, California.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, to protect against espionage and sabotage. Notices appeared ordering people of Japanese descent to report to civil stations for transport.

Desperate families sold off belongings for cheap and packed what they could. The luckier ones had white friends who agreed to care for houses, farms and businesses in their absence.

"Others who couldn't pay their mortgage, couldn't pay their bills, they lost everything. So they had to pretty much start from scratch," said Rosalyn Tonai, 56, executive director of the National Japanese American Historical Society in San Francisco.

Tonai was shocked to learn in middle school that the U.S. government had incarcerated her mother, aunts and grandparents. Her family hadn't talked about it. Her mother, a teenager at the time, said she didn't remember details.

Her organization, the Japanese American Citizens League and others oppose the use of the word "internment." They say the government used euphemisms such as "internment," ''evacuation," and "non-alien" to hide the fact that U.S. citizens were incarcerated and the Constitution violated.

The groups say this White House has what they see as the same dangerous and flippant attitude toward the Constitution. Japanese-American lawmakers expressed horror when a Donald Trump supporter cited the camps as precedent for a Muslim registry.

The Japanese American Citizens League "vehemently" objected to executive orders signed by Trump last month, to build a wall along the Mexican border, punish "sanctuary" cities that protect people living in the country illegally, and limit refugees and immigrants from entering the country.

"Although the threat of terrorism is real, we must learn from our history and not allow our fears to overwhelm our values," the statement read in part.

Hiroshi Kashiwagi was 19 when his family was ordered from their home in Northern California's Placer County and to a temporary detention center.

He remembers slaughtering his prized chickens- New Hampshire Reds- for his mother to cook with soy sauce and sugar. She stored the bottled birds in sturdy sacks to take on the trip. The family ate the chickens at night to supplement meals. The birds didn't last long.

Today, Kashiwagi, 94, is a poet and writer in San Francisco who speaks to the public about life at Tule Lake, a maximum security camp near the Oregon border. Winters were cold, the summers hot. They were helpless against dust storms that seeped inside.

"I feel obligated to speak out, although it's not a favorite subject," he said. "Who knows what can happen? The way this president is, he does not go by the rules. I'm hoping that he would be impeached."

Orders against Japanese-Americans were revoked after the war ended in 1945. They returned to hostility and discrimination in finding work or places to live.

A congressional commission formed in 1980 blamed the incarceration on "race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership." In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill to compensate every survivor with a tax-free check for $20,000 and a formal apology from the U.S. government.

Ina said that only then did her mother, Shizuko, feel she got her face back, her dignity returned. By then her father, Itaru, had died.

"This is a burden we've been carrying, and if we can make that burden into something meaningful that could help and protect other people, then it becomes not so much an obligation but more as a responsibility," Ina said.

After Trump's election, Ina vowed to reach out to the Muslim community and protest and tell everyone about what happened to her family. She brought her message to a gathering of camp survivors in the Los Angeles area.

"And this old woman, she had a cane, she said, 'OK. I'm going to tell everybody about what happened. This is very bad. It's happening again,'" she said. "It's that kind of spirit."

In this Feb. 10, 2017 photo, Satsuki Ina holds up an identification tag issued to her mother, Shizuko Ina, at her home in Oakland, Calif. As Japanese Americans mark the 75th anniversary of the executive order that authorized their incarceration, they're speaking out against new presidential orders that limit travel and target immigrants. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

The Associated Press

This 1945 photo provided by the family shows Shizuko Ina, with her son, Kiyoshi, left, and daughter, Satsuki, in a prison camp in Tule Lake, Calif. This photo was made by a family friend who was a soldier at the time, since cameras were considered contraband at the camp. Satsuki was born at the camp. (Courtesy of the Ina family via AP)

The Associated Press

This Feb. 10, 2017 photo shows Satsuki Ina at her home in Oakland, Calif. Ina was born behind barbed wire in a prison camp during World War II, the daughter of U.S. citizens forced from their home and locked up for years following Japanâs attack on Pearl Harbor. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

The Associated Press

FILE - In this April 6, 1942 file photo, a boy sits on a pile of baggage as he waits for his parents, as a military policeman watches in San Francisco. More than 650 citizens of Japanese ancestry were evacuated from their homes and sent to Santa Anita racetrack, an assembly center for war relocation of alien and American-born Japanese civilians. (AP Photo)

The Associated Press

In this Feb. 10, 2017 photo, Hiroshi Kashiwagi speaks during an interview at his home in San Francisco. Kashiwagi was 19 when his family was ordered from their home in Northern Californiaâs Placer County and to a temporary detention center during World War II. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

The Associated Press

FILE - This May 23, 1943 file photo shows a Japanese relocation camp in Tule Lake, Calif. Tule Lake is at left, under Mount Shasta. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to desolate camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. Thousands were elderly, disabled, children or infants too young to know the meaning of treason. Two-thirds were citizens. (AP Photo)

The Associated Press

In this Feb. 10, 2017 photo, Hiroshi Kashiwagi holds 1945 photos of himself at an internment camp in Tule Lake, Calif., at his home in San Francisco. Today, Kashiwagi, 94, is a poet and writer who speaks to the public about life at Tule Lake, a maximum security camp near the Oregon border. Winters were cold, the summers hot. They were helpless against dust storms that seeped inside. "I feel obligated to speak out, although it's not a favorite subject," he said. "Who knows what can happen? The way this president is, he does not go by the rules. I'm hoping that he would be impeached." (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

The Associated Press

FILE - This March 23, 1942 file photo shows the first arrivals at the Japanese evacuee community established in Owens Valley in Manzanar, Calif., part of a vanguard of workers from Los Angeles. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. (AP Photo/File)

The Associated Press

In this Feb. 10, 2017 photo, Hiroshi Kashiwagi speaks during an interview at his home in San Francisco. Kashiwagi was 19 when his family was ordered from their home in Northern Californiaâs Placer County and to a temporary detention center during World War II. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

The Associated Press

FILE - In this June 19, 1942 file photo, Japanese evacuees move into a war relocation authority center in Manzanar, Calif. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to desolate camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. (AP Photo/File)

The Associated Press

FILE - In this March 30, 1942 file photo, Cpl. George Bushy, left, a member of the military guard which supervised the departure of 237 Japanese people for California, holds the youngest child of Shigeho Kitamoto, center, as she and her children are evacuated from Bainbridge Island, Wash. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to desolate camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. (AP Photo/File)

The Associated Press

FILE - In this March 21, 1942 file photo, people of Japanese ancestry board buses in Los Angeles, for Owens Valley, 235 miles north, where the government's first alien reception center is under construction. The nearly 100 people were skilled workers who will help prepare the camp for thousands of others to arrive later. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to desolate camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. (AP Photo/File)

The Associated Press

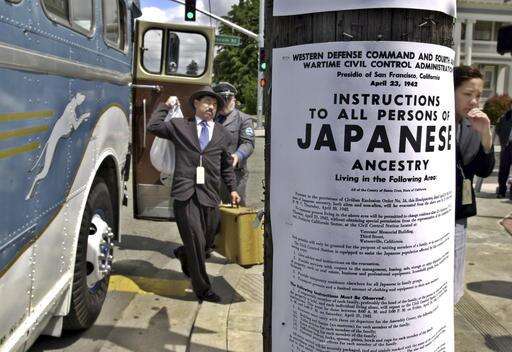

FILE - In this April 27, 2002 file photo, a copy of a poster from 1942 is posted in front of an antique Greyhound bus in downtown Watsonville, Calif., as participants reenact what happened to their relatives exactly 60 years earlier during their internment in 1942. Roughly 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans were sent to desolate camps that dotted the West because the government claimed they might plot against the U.S. (AP Photo/Paul Sakuma, File)

The Associated Press